Your duty is to exhaust.

I really believe that artists are here to not just become a carrier for desires that have already brought us here

The process of valuation, he said, ran in terms of salesmanship and all the traits of character that depended for their success on taking advantage of people’s weaknesses. It gave rise to a pragmatic point of view, with “pragmatic” meaning the agent’s preferential advantage at the expense of others.

Veblen’s “anthropological” discussions were in fact contemporary delvings into the nature of the modern money economy under the guise of anthropology. His description of the barbarian’s standard of success in terms of skulls led up to his description of the modern man’s standard in terms of money. And modern ownership, as in effect an ownership and enslavement of persons by pecuniary masters, he analyzed most sharply under the guise of a discussion of the barbarian status of woman as a chattel of the ferocious warrior.

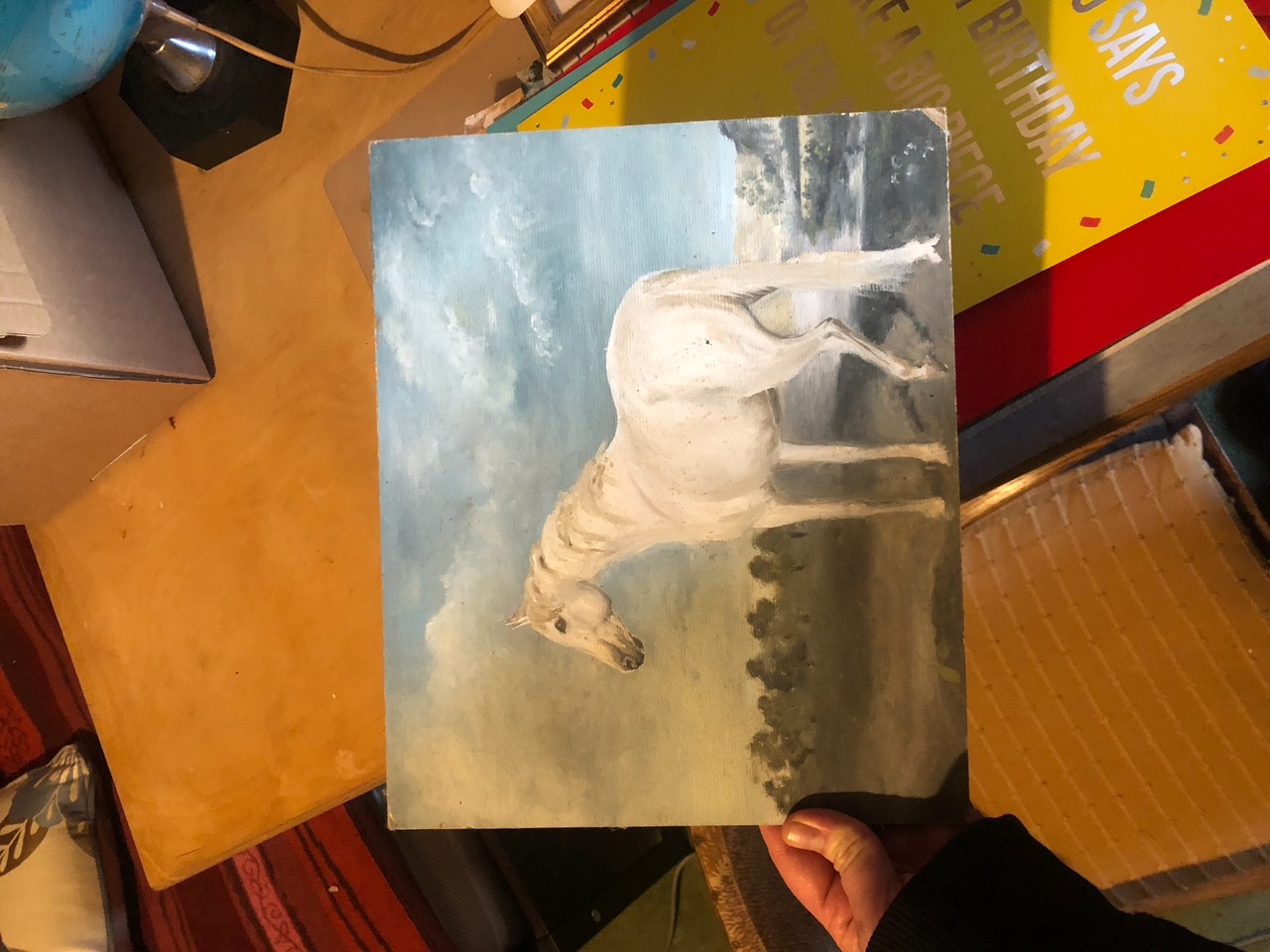

The contrast between “business” and “industry” was worked out in the strangest guises — dress versus clothing; the higher learning versus the lower learning; pecuniary beauty versus economic beauty; pecuniary canons of taste versus aesthetic canons of taste; predatory dogs versus peaceful cats; medicine men versus modern scientists; athletic combats versus physical education; criminals versus the industrious; the patriarchal family versus the household of the unattached woman; and, most sharply of all, the ferocious barbarian age versus that “earlier” stage, the presumptively primitive age of peaceable and free savages.

The free savage suddenly seemed superior; Veblen, on top of all else, was something of an anarchist. At least intermittently he showed a lack of sympathy for the “animated slide rule” or “finikin skeptic” of modern science, and for the impersonalization of large scale industrial and social organization. An occasional pessimism regarding progress crept through; and he waxed eloquent on man’s inherited human nature was being restrained to meet the requirements of modern technology. He had an undercurrent of sympathy for that golden age when man, if he was not completely rational, was at least not predatory. “As seen from the point of view of life under modern civilized conditions in an enlightened community of the Western culture, the primitive, ante-predatory savage . . . was not a great success. Even for the purposes of that hypothetical culture to which his type of human nature owes what stability it has . . . this primitive man has quite as many and as conspicuous economic failings as he has economic virtues as should be plain to anyone whose sense of the case is not biased by leniency born of a fellow-feeling. At his best he is ‘a clever, good-for-nothing fellow.’ The shortcomings of this presumptively primitive type of character are weakness, inefficiency, lack of initiative and ingenuity, and a yielding and indolent amiability, together with a lively but inconsequential animistic sense. Along with these traits go certain others which have some value for the collective life process, in the sense that they further the facility of life in the group. These traits are truthfulness, peaceableness, good-will, and a non-emulative, non-invidious interest in men and things.”